This piece was originally published in First Monday Volume 22, Number 3–6 March 2017.

Abstract

As technology becomes smaller, the way we carry it has progressed from luggable, to wearable and now towards devices that reside inside the human body, or insertables. This trend is particularly observable in many medical devices, such as pacemakers that were once large stand-alone devices and are now completely inserted into the body. We are now seeing a similar trajectory with non-medical systems. While people once carried keys to open office doors, these have been mostly replaced with wearable access dongles, worn around the neck or clipped to clothing. Some individuals have voluntarily taken the technology from these dongles and inserted it directly into their body. We introduce insertables as a new interaction device of choice and provide a definition of insertables, classifying emerging and near future devices as insertables. We demonstrate this trajectory towards devices inside the human body, and carve out insertables as a specific subset of devices which are voluntary, non-surgical and removable.

Introduction

Humans have been altering their bodies’ for millennia, through markings on their skin and objects piercing their body. Tattooing and scarification have been practiced since ancient Egypt in 3,000 BCE. Similarly, lip disks, or lip plates, often seen in African tribes, date back to 8,000 BCE. We also have evidence of body modification during in Biblical times, when a golden nose ring (i.e., body piercing) was given as a gift to Abraham’s future wife (Genesis 24:22). Body augmentation for aesthetic reasons continues today.

Lip disks, scarification & piercings have been practised for millennia

Within the last century new objects have been inserted into the body for restorative medical purposes. These objects include stents, pacemakers, insulin pumps, prostheses, cochlear implants, drug delivery pumps, spinal cord stimulation, and deep brain stimulation to name but a few. More recently, individuals have been modifying the body with ‘subdermal or transdermal implants’ for non-medical reasons, predominantly in the form of radio frequency identification (RFID) microchips and near field communication (NFC) microchips.

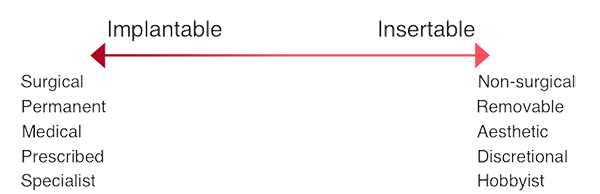

We use the term insertables to refer to this category of devices that are contained within the boundaries of the human body. Insertables are objects that go in, though and underneath the skin. This is in contrast with wearables which are objects worn with clothing or on the body. Our choice of the word insertable, over the less controversial ‘implantable’, is deliberate. The word implant is derived from the Latin implantare meaning engraft or to plant, while insert has a gentler origins from the Latin inserere: to put in. Implantable is often used in the medical context to refer to an object fixed in a person’s body by surgery. Therefore, implantables are more difficult, if not impossible, to remove while insertables are minimally invasive to insert and remove. An implant is often something done to a person, whereas an insertable implies a strong sense of personal agency and choice. Insertables are differentiated from implantable by their voluntary and non-medical nature (see Figure 1, for comparison of implantables and insertables).

Figure 1 Continuum of devices: Implantable to Insertable

From wearable to insertable

Personal electronic devices were making a transition from luggable to wearable. We now propose these devices are entering a new phase: insertables. The progression towards insertables can already be seen in in many arenas. In this section we highlight examples of devices that were once luggable and wearable and have now become implantable or insertable.

Heart rhythm

Pacemakers, life saving devices that enables ones’ heart to be regulated where it is otherwise not functioning properly, have progressed from heavy luggable machines to small wearable instruments and now are fully implanted inside the body. The first pacemakers were large luggable devices that were plugged in to an electric socket and bought to a patient. An insulated needle was then inserted into the patients’ heart and electrical pulses were delivered directly into the affected chamber. The next evolution of pacemakers was a wearable device. The external pacemaker had pins that were implanted in the heart and attached to external leads that were powered by a battery-operated pulse generator. This generator was small enough to wear on a belt buckle and walk around with, leading to a more normal life. Today’s pacemakers, known as implantable cardioverter devices (ICD), are concealed entirely in the body, including the pulse generator and battery. ICD installation is now routine surgery, with surgical battery replacement needed every 10 years or so.

Evolution of the Pacemaker

Insulin regulation

Similarly, insulin pumps, devices that are used to monitor blood glucose levels in diabetics and take restorative action when they deviate from equilibrium by releasing insulin, have made this transition from luggable. Prior to insulin pumps patients would need twice daily intramuscular injections. Vials of insulin were lugged in syringe kits to be administered. Early wearables for diabetics were portable infusion pumps, allowing for continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. Technological advances have seen smaller and smaller iterations of these devices, to the point that patches of insulin can be attached to the body which are then controlled wirelessly by a remote device. Research is currently underway to create internal insulin pumps without the need for an external control, such as the University of Delaware’s B-smart device.

Evolution of Insulin regulation devices

Prostheses

Limb replacement aids have developed from luggable wheelchairs and crutches to wearable and now partially insertable prostheses. Early prostheses date back to the ancient Egyptians; replacement body parts were created for aesthetic reasons from wood and leather. These prostheses were non-functional and were crudely attached to the body. The next iteration of prostheses were still attached to the body, but offered some function and range of motion. Modern prostheses have components that are inserted into the body, and are no longer purely wearable. They attach to the body for neural sensory feedback. Some prosthesis even include microchips to gather post-op data for rehabilitation and research into brain-machine interfaces is ongoing for full neural control over prostheses.

Evolution of limb replacement solutions

Vision

Vision correction and improvement devices in optometry have followed the luggable to wearable to insertable trajectory. It has been hypothesized that prior to glasses the ancient Egyptians would lug gems or glass vessels of water for magnification. Eyeglasses, in the form of wearables, emerged around the fifteenth century and have had many advances and fashion trends since in the form of bifocals, monocles and transition lenses. Vision correction has since bridged into contact lenses, which are inserted under the eyelid.

Evolution of vision aids

Hearing

Early hearing aids were a luggable horn called an ear trumpet, first described in 1558. Modern hearing aids are wearable devices which are worn within the ear to amplify sound. Insertable hearing aids and cochlear implants are now available which are surgically implanted around the cochlear in the inner ear to vibrate it when driven by an electromagnetic field.

Evolution of hearing aids

Animal identification

This evolution from wearable to insertable been seen in animals, both pets and livestock. RFID transponders are attached to livestock to keep track of them in a way that was not possible before. Pet microchipping is a now common and accepted practice in pets, and is indeed a legal requirement in some states and countries, removing the need for wearable tags on collars. SureFlap is providing microchip pet doors and pet feeders that work with existing microchips on pets, removing the need for additional pet wearables.

Insertables as a device of choice

Many of the above examples are types of internal medical devices (IMDs), which provide benefits to patients by allowing them to live relatively normal lives again. The IMDs reduce the burden of illness and provide the ability to keep illness hidden by having the device inside the body. In these medical situations, there is often little choice of whether or not to use an IMD. The driver is typically the result of a medical need, not a discretionary want.

We now see non-medical products become acceptable as insertables out of personal preferences. The difference is that these devices are no longer only for restorative purposes, but for convenience. Individuals can choose wearable or insertable forms based on their personal preferences. Eyeglasses can be worn or contact lenses inserted. It is important to remember that the impact of eyeglasses were hotly debated in their time, but now we accept them, and contacts, as part of everyday life. The social stigma associated with some insertables has been neutralized with time.

Wearable and insertable modes can co-exist. For example, wearable hearing aids and implantable hearing aids co-exist with individuals being able to choose which they prefer, if any; indeed there is a considerable movement in ‘deaf culture’ to remain electively deaf. Contraceptives concurrently exist both as wearable prophylactics in the form of male condoms, or insertables contraceptives in the form of female condoms, diaphragms, intrauterine devices (IUD) and sub-dermal contraceptive implants. Menstrual aids too come in wearable or insertable form, with an individual able to choose which they are more comfortable with: pads, tampons or menstrual cups.

With the acceptance of insertable objects in the body shown above (contraceptives, menstrual aids, body piercings and other body modifications) we are beginning to see voluntary insertion of, and emergence of, digital insertable devices. Indeed, LoonCup is a smart menstrual cup, showing this trend towards digital insertables is already beginning.

Experimenting with insertable devices

The concept of this rise in digital insertables is not new. The earliest recorded prediction of digital devices being inserted within human bodies comes from Dr. Alan Westin, who in 1967 spoke of “the possibility of ‘permanent implacements of ‘tagging’ devices on or in the body’”. Several decades later, in 1999, electrical engineer and researcher Larry McMurchie opined that inserted devices is a reasonable extension to wearable ones:

It’s not a big jump to say, ‘OK, you have a wearable, why not just embed the device’

In 2000, x-BT researcher Peter Cohrane foretold of

A day when chips are not just worn around the neck, but are actually implanted under a human’s skin

These predictions were again echoed in 2003:

From a purely ‘rational’ point of view, it would make sense to implant a small chip under the skin, rather than have it on a card that can easily be lost

The first forays into human microchip implantation occurred in 1998 with Kevin Warwick implanting himself with an RFID capsule in his Cyborg 1.0 experiment. Warwick’s chip opened doors and activated lights in his office for the duration of the experiment. The same year artist Eduard Kac self-inserted RFID microchips in an art piece entitled ‘Time capsule’.

Over a decade later, VeriChip, began selling and inserting an FDA approved RFID chips for patient identification and medical record recall in hospitals. While VeriChip installed RFID readers at 900 U.S. hospitals, and claimed over 2,000 sales, the practice did not reach widespread proliferation. Although use for medical identification was not common, the availability of VeriChips spawned other small-scale initiatives. For example, implanting VIP patrons at the Baja Beach Club in Barcelona for VIP room access and point-of-sale purchases, and implantation of 160 employees of the Mexican Attorney General’s office.

The VeriChip included a bio-bond coating to graft to human tissue to stop migration. This rendered removal of the chip very difficult, if not impossible. This sense permanence of the device inside body is more akin to an implantable, rather than an insertable, which should be easily removable. The possibility of using removable devices heralded the rise of insertables hobbyists. Individual hobbyists have been experimenting with devices under the skin since Amal Graafstra engendered the current hobbyist movement in 2005 by sourcing chips without the bio-bond coating found the the VeriChip device. This movement continues through his Web site, DangerousThings.com (http://dangerousthings.com), that sells devices to the public who can self-insert or seek medical practitioner or body modification artists’ assistance to insert them. There are entire forums and Facebook groups dedicated to individuals interested in getting implants (biohack.me, http://biohack.me) and the movement is continually growing. Several companies now sell insertables such as cyberise.me (https://cyberise.me) and chipmylife.io (https://chipmylife.io).

Choosing insertables

Insertable devices in humans seem to offer significant convenience. Individuals no longer have to remember to lug keys, or wear an access dongle, but can use insertable devices to authenticate themselves at office doors. Having a device inserted under the skin, to avoid carrying keys, may seem extreme but

Convenience and time have been persistent tempters to us before

and

As has been demonstrated by cosmetic surgery, we cannot assume that because a procedure is highly invasive people will not undergo it

Certainly, when compared to cosmetic surgery, inserting a microchip into the skin of the hand is almost non-invasive; it is less invasive as a body piercing. These microchips are being used by thousands of individuals for access and authentication to buildings (home and work), NFC compatible phones, car and motorcycle access. They are also being used to store and transfer small amounts of data to compatible devices. Implanted magnets are used to sense electromagnetic fields. Science fiction too has prepared people for possible futures with insertables — leading to implicit knowledge of how to operate them, yet also unfounded fears and expectations of GPS tracking abilities.

Classifying insertables

As we have illustrated, there many examples of personal devices that have evolved from luggables towards insertables. Just as luggables define a large sub-set of objects (desktops, laptops, telephones, tablets etc.), insertables also characterize a class of devices that go through or under the skin or otherwise inside a person. We use insertables to refer to this category of devices that are contained within the boundaries of the human body. This includes devices inserted into, and removed from, cavities of the body easily by the individual, and those that must be inserted by medical professionals or qualified body modification artists. The classification of insertables includes:

- ‘Smart’ body jewellery

- ‘Smart’ contact lenses

- ‘Smart’ menstrual aids

- Emerging insertables such as RFID and NFC microchips and neodymium magnets

Devices which are removable and voluntary, but still provide medical benefits blur the line between insertable and implantable, for example: implantable contraceptive and pharmaceutical delivery devices; dental implants and orthodontics; prosthetics; pessary and suppository devices, and; swallowable devices that are temporarily traversing the insides of a body, for example diagnostic pill cameras. Re-appropriating RFID and NFC chips, and inserting them against ones will (for Alzheimer’s wandering alerts, for prisoner checkpoints and other nefarious purposes) is not only ethically questionable, but unlawful in many parts of the world under pre-emptive U.S. laws against forced microchipping in at least 17 states including California, Wisconsin and Rhode Island. In the U.K. forced insertion would likely fall under their anti-mutilation laws.

As in biology, classification is important to understand the interconnections between similar items. Classifying all these devices as insertables means that standards, design and ethical considerations can be made at scale for all devices that go through the human body, rather than tackling each individual devices as a separate case.

Our classification does not include recent innovations, that are comparable to insertables but are more accurately classed as wearables. Such innovations include: NailO, an input device that attaches to a finger nail developed by Kao, et al. (2015); iSkin, body touch sensors that go over existing skin, developed by Weigel, et al. (2015) or DuoSkin an on-skin device. Nor does it include biometrics, smart eyelashes, conductive make up, heart authentications using ECG devices, and smart tattoos. These technologies must be put on to the body, not inside the body. Insertables are the only ubiquitous devices that can truly always with a person as they are physically inside the body.

Future research

There is still a great deal to learn about insertable technologies. We do not know the types of insertable devices individuals are carrying, nor how the devices are being used. Future research should seek to understand what individuals are inserting and why. Reasons for inserting, and particularly for choosing an insertable over an available wearable device should be better understood. Specific questions for future research include:

- What are the characteristics of individuals using insertables?

- Why do individuals decide to modify their bodies instead of using wearables?

- What are the kinds of insertables they are using and what capabilities of the device do they wish to exploit?

- How are insertables used to interact with existing computing systems?

Conclusion

While not every device can, or will, become insertable, and not every person will want to get an insertable device, we have demonstrated the evolution of devices from being lugged by a person, to worn on a person and now being contained within a person. This trend towards insertables has been seen in the form of IMDs and towards voluntary insertable devices in individuals that chose to augment their bodies. This research has also defined and classified insertables as a category of device, separate from wearables, and disctinct from other implantable devices.

References available in original paper on First Monday

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5210/fm.v21i13.6214