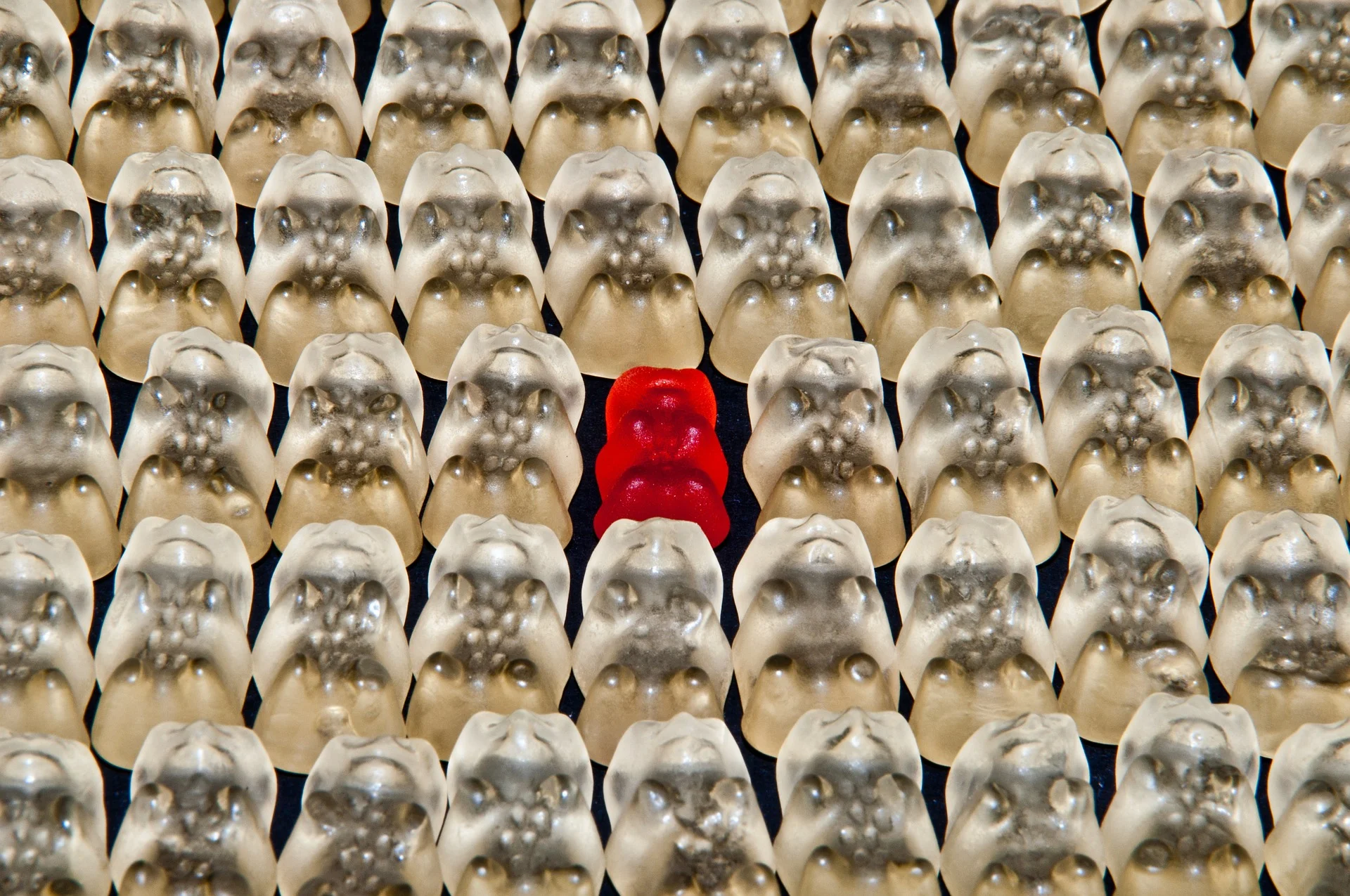

We use colour as a signifier for people, places and things all the time. Probably more than you realise. About 8% of Australian males and 0.4% of females are colour blind. Like all people with ‘disabilities’, there are certain things colour blind people can’t do. Design can help make the world more accessible to ensure they can do everything those with ‘normal’ vision can. I explore ways to deign for colour blind users, which often improves the experience for everyone.

Does the NPS tell us what users really mean?

Design is as good (or as flawed) as the people who make it

gave a talk at UX Australia 2016 in Melbourne (August 25–26) . No one sets out to intentionally design a system that is hard to use for — or worse, excludes or discriminates against — some users. Designers are trying their best. You’re probably a good person, but a human nonetheless, therefore not perfect. Design can only be as good as the people who make it. Conversely, design is as flawed as the people who make it.

Drunk Kayla & Uber UX

You put what, where? Hobbyist use of insertable devices (Part 2)

The human body has emerged as more than just a canvas for wearable electronic devices. Technological size and cost reductions, along with power and battery improvements, has meant items that were once external have become wearable, and even insertable.

In part 2 we look at our results - what are participants inserting and what does this mean for the future of HCI & UX?

You put what, where? Hobbyist use of insertable devices (Part 1)

The human body has emerged as more than just a canvas for wearable electronic devices. Technological size and cost reductions, along with power and battery improvements, has meant items that were once external have become wearable, and even insertable.

Part 1 gives background to my research to be presented at the CHI conference in San Jose this week.

Guys — one month on

PSA - "He" is not a substitute for "they"

Guys as the new ‘um’

Gendered words can be, and are, damaging to some recipients (and effectively the deliverer). You’re probably not even aware of the fact that you’re alineting or demeaning your audience. I, and a lot of other women, have a visceral reaction to the term and it’s important you are aware of the impacts of choosing to using it. Let's talk about "guys".

Insertables: I’ve got I.T. under my skin

An intro to Insertabeles, as published in ACM interactions.

Imagine Dylan, a bureaucrat working in a foreign embassy. Dylan approaches a security door, arms overflowing with confidential reports. Dylan leans toward the door’s access sensor and is authenticated. The door is now unlocked and can be easily pushed open with one shoulder, without the need to put down the documents and fumble for his keys or an access pass. Dylan has an insertable device implanted subcutaneously in his hand that interacts with the transponder at the office door.

It may read as science fiction, but it's already a reality.

Superhuman abilities could lurk under your skin

Looking towards 2016

Automagic Revisited

Last Xmas I (gave you my heart) wrote a piece about The Phenomenon of Automagic. I defined Automagic as when your users don't know how your app is working - it just works. Last week I was the OzCHI (The Australian Human Computer Interaction Conference) and Abi Sellen from Microsoft Research opening Keynote made me give automagic a second thought.

Insertable & Implantable Tech workshop

Building User Empathy Within Product Teams

Creating Delight - put yourself in the users shoes

Stop blaming your users

What I learned when I asked 15 young women about their photo sharing habits

The Fold Still Matters... Sometimes

In early web design we always used to talk about the "fold" - the part of the screen a user will see without scrolling down the page. Many think those who still consider the fold to be old school and outdated, but sometimes the fold still matters. If your website isn't the main goal you still need to consider the fold.